PROBABLY PRIVATE

Issue # 3: Election Disinformation and Privacy

Hi folks, and welcome to the third issue of Probably Private!

I've been a bit preoccupied with the US election, my work and the ever rising European COVID19 numbers, hence the delay in this issue. Thanks for your patience — I'm going to aim to get back on track, if only to have a fun part of my week focused on my passion for privacy in machine learning and data science (and adjacent musings).

For today's issue, I am experimenting with some new format ideas and fresh content. A deeper dive into one specific topic that is near and dear to some of the anxiety we are all experiencing right now. Information disorders and how they interact with things like privacy and data science.

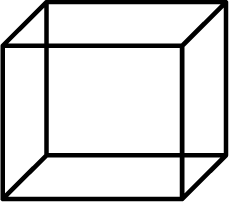

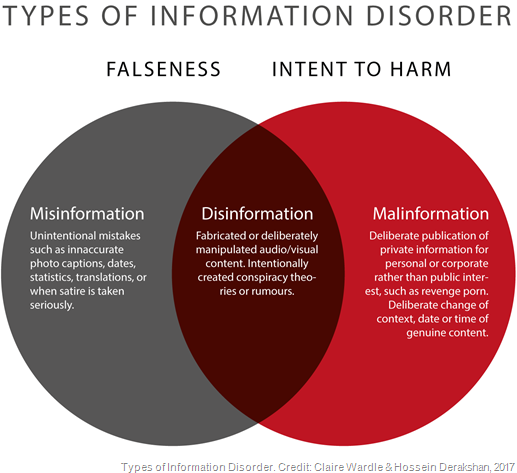

For a quick definition of what I mean by information disorders, this graphic helps a lot:

It's increasingly apparent (especially in political conversations) that disinformation is a constant and growing influence on our world. To be clear, this isn't necessarily a new phenomenon, but the ability to quickly spread false information (intentionally or unintentionally) is enhanced by social media and messaging platforms, where you can easily mass-forward or message many people at once. These nodes of our social graph can then quickly spread and influence other adjacent groups. I hear something, I want to share it with my friends and family, and so on. This, again, is not new - it has just gotten faster and easier.

And sometimes how this misinformation or disinformation chain starts occurs outside of social media in content-based networks like YouTube, Google Search or Amazon via recommendation algorithms (or honestly, any highly politically motivated media network or content platform). What these platforms then allow is for content creators and curators to create disinformation or misinformation campaigns that, depending on their level of virility, turn clicks into cents. This, of course, incentivizes more incendiary content and a baiting of the recommendation and search algorithms the same way we've seen via SEO destroy our ability to easily search and find results over the past 30 years. If I know that you'll be searching for a new word that Trump used, I'll immediately create a YouTube video for it, promote it on Twitter with hashtags or on Facebook, reply with it linked on other channels. I do this in hopes it goes viral and I earn money (maybe I am also motivated by the message as well, so there can be added incentives here).

Of course, some of this is also state-sponsored and organized by large political groups themselves. It is clear that this type of voter manipulation was becoming more widespread when Cambridge Analytica scandal broke and it showed exactly how many organizations were profiting directly from psycho-analytics + targeted advertising. What is disappointing is how unregulated or unaddressed this type of advertising still is today — despite the attention from our years ago.

But, what I think was under-reported and under-discussed was the interaction of these psycho-analytics and profiles and privacy. Sure, we had lots of conversations about the ethics of using private information to target individuals, but I don't think we talked enough about how that happened and what enabled that to happen from a machine learning and data science point of view.

What we've been able to do using machine learning and data for awhile now is to correctly infer private information about individuals based off of how they browse, click, message, share, like, even what apps they use... What this means is that even if you don't tell me your age, race, sexual orientation or gender, there's a good chance I can guess it given some of the ways you behave online. And it's not just you, and it's not just those details. And this, my friends, is where we have a huge problem.

You see, regulation covers the private information that you give to a company and that company asks you for your consent to do things with. That's fine. But what isn't yet clear enough is what about "information derived from that information". This quickly becomes a gray area, especially if it cannot be considered a specific privacy or targeting risk for you as an individual. And if a company DOESN'T ask your political orientation but this can be derived by how you use the service, then it could be argued that this falls under "value that the company added to your data", which under GDPR and other regulations means it belongs to the company and not you. You can hopefully start to see that this is a very slippery slope we are on and that, if we get even better at inferring sensitive information for most people (something a lot of folks in adtech and recommender systems are working on), then this becomes a huge unregulated area where private information is a value add for a company, and is not something controlled or consented to by the individuals or the collective society.

So, the problem of disinformation, misinformation and privacy, is that targeting networks which try to infer what you might buy, have gotten quite good at guessing things they might not know (or want to ask) about your private information. In fact, in many cases, these inferences might not be explicitly recorded, but are used as a collection of aggregated features that are based on how you behave that can allow a targeting network to infer something about you that you might not even publicly admit yourself. And these ad- and content-targeting systems can now be used to influence how you might vote, how you might think, what you believe about yourself and the world and what you perceive as true and false. Don't get me wrong, I was worried about this phenomenon (and I think you should be too), when it was just used to sell a thing, but using it to sell an idea, to influence national and international politics, to alter the course of societies and histories is an entirely different thing altogether. And, as we can see in the US right now, it is dangerous — for everyone.

Despite the severity, I think there are some interesting developments that could help address these issues

I am, as always, hopeful that these problems, created by data science and machine learning tactics being used for unethical, unfair and in-transparent purposes can be solved. Your time reading this issue is proof enough to me that there are people who are motivated to learn and hopefully also motivated to push for change. 🙂

Thanks for your time today — as always, I look forward to the conversation! Please feel free to reach out on social media (lol) or reply here and tell me if you liked this newsletter! Again, I am still experimenting with length and content, so your feedback (even a sentence!) is super helpful as I find the Probably Private voice and cadence.

With Love and Privacy, kjam

With Love and Privacy, kjam