PROBABLY PRIVATE

Issue # 22: Measuring Privacy in Deep Learning

Hello privateers,

How is your February starting? It's been very cold and icy in Berlin (and many other places), I hope you are staying warm and safe.

Two quick announcements before we dive in this month. I'll be co-hosting the Feminist AI LAN party again at this year's PyConDE. Ines and I need volunteers, IT crew, computers and cool workshops, so please reach out if you want to join or help out.

Want to learn Practical AI Privacy with me? You can now enroll in my online masterclass on Maven which will run from late April through May with hands-on practice to integrate privacy into today's AI products and systems. There's also a free lightning lesson on March 4. Ping me if you have questions!

This newsletter is the last (for now) in our exploration of differential privacy in deep learning. Differential privacy is proven to reduce memorization in AI models and reduce the privacy attack surface. But using it in deep learning is not standard practice, yet.

In my experience one of the sticky points in discussions is parameter choice and accounting. To help demystify these bits, let's explore it together.

When using differential privacy, you have to choose your privacy parameters, like your epsilon (ε). Depending on your implementation, you might have other parameters and noise distribution choices as well (such as Gaussian vs Laplace).

In DP-SGD, there's a proven way to track your privacy budget (i.e. how much ε you spent on the last round of training). It's called the moments accountant and uses a clever way to perform the necessary clipping and scaled Gaussian noise sampling for each mini-batch.

Why is it called "moments"? Researchers found that it's easiest to calculate bounds for Gaussian noise by recording its moments. A moment is a particular measurement of a variable that helps you understand the properties of the underlying function or distribution.

For a Gaussian distribution, the first moment is the mean, the second moment is the variance, and higher-order moments (3 and 4) can provide information about the skewness and kurtosis; however, there are even higher moments you can measure which continue tracking the underlying distribution properties.

Let's dive into how the moments accountant works:

Based on ideal spend for the two parameters (epsilon and delta) and the clipping value (which is the gradient norm of the mini-batch), a Gaussian distribution is formed to add noise to the clipped gradient. These parameters inform the standard deviation of the Gaussian noise distribution, because they balance how much you are willing to spend and how sensitive the data in that mini-batch is.

Several moments (i.e. 3 and 4, for example, but you can go up to a very high number of moments) are recorded for that noise distribution and stored by the accountant.

Training continues, performing steps 1 and 2 for each mini-batch.

At the end of an epoch, sum the moments accumulated and calculate the upper bounds of this epoch's training rounds based on those values. This reverse engineers the epsilon spent in that epoch.

If the target epsilon is reached, you can stop training. Otherwise training epochs can continue. Usually the accountant will display the information via a log message per epoch.

In this way, deep learning methods allow you to also go "over budget" since the actual spend is based on the moments and not the "ideal spend" that helps calculate the noise. Some of the more popular libraries for deep learning with differential privacy, like Opacus, let you determine if you stop or keep learning when your target budget is reached.

When doing deep learning, your budgets will be higher compared with many other implementations. That said, research shows that differentially private learning reduces the impact of memorization, makes MIAs more difficult, and extraction attacks almost impossible.

To prove this outside of research, differentially private learning needs to become more of a norm when training with sensitive data. Additionally, better testing for memorization and privacy leakage and better use of privacy technology in real-world AI/ML problems can help provide more proof and easier implementation.

This might mean incorporating MIAs and extraction attacks as part of the model evaluation and validation step. Imagine if privacy testing became a normal part of model release and that those figures could be used to evaluate which open weight model you choose.

This testing could be added to the training software and MLOps stack. Pollock et al. proved that looking at loss distribution across training examples during training rounds can identify a significant proportion of the memorized and at-risk examples. They released their work on GitHub.

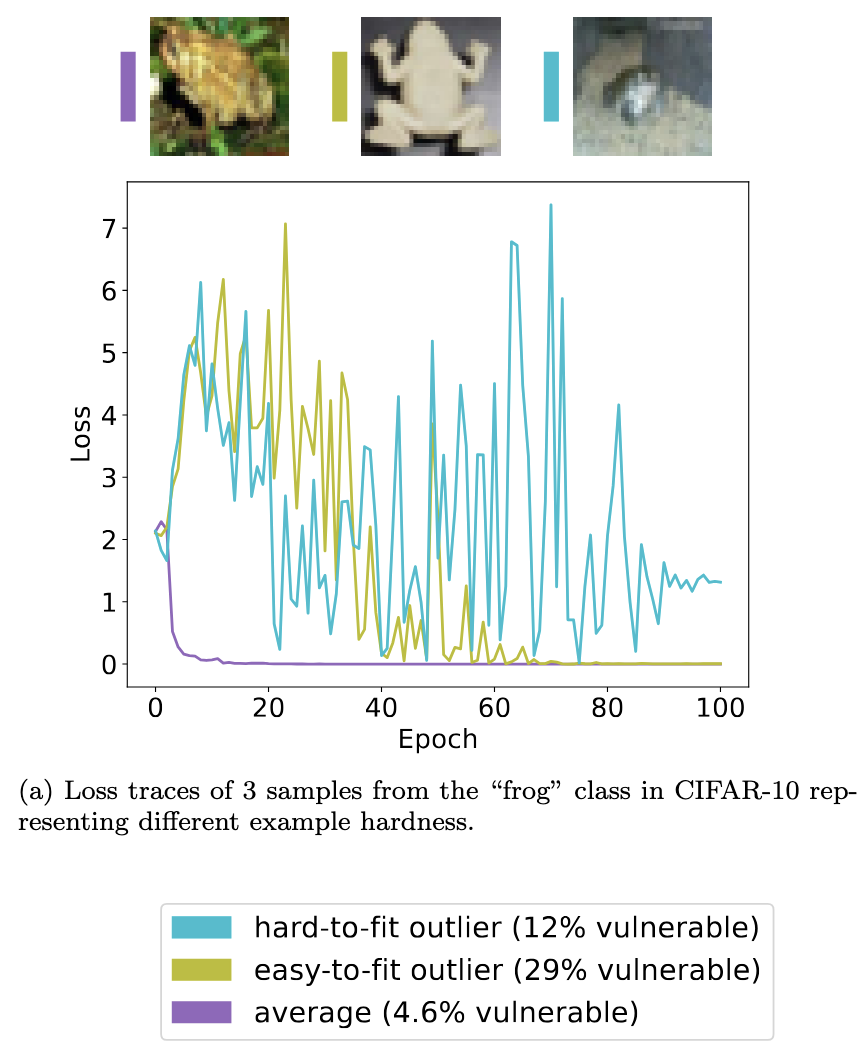

This is a visual from their paper, showing three different types of frog images in CIFAR-10. One is average (lost in the crowd), one is an easy-to-learn outlier (not complex) and one is difficult to learn (complex). The authors note the success rate of MIAs targeting these examples, showing that the outliers have a higher risk of being identified.

The loss traces are shown in the graph, where the average example has a quite stable and early loss drop. The easy-to-learn outlier loss shows less stability in early and middle epochs, but eventually stabilizes. In comparison, the hard-to-learn outlier's loss almost never stabilizes and it might not have been fully learned (based on the loss and the MIA success rate).

This privacy observability could be added to training as a way to highlight potentially problematic examples. There are similar approaches that look at gradient leakage during training.

In the longer article on this topic, I dive deeper into why differential privacy auditing matters and showcase several interesting papers on the topic of privacy testing and accounting. I can also recommend reading Damien Desfontaines' latest article on 3 types of privacy auditing, that dives into some of these distinctions.

I've been releasing videos and posts on how to set up your own personal AI lab, so you can better control how you use AI/ML systems and learn more about what workflows work for you.

In addition, keeping (most) of your data local can improve your privacy and security guarantees.

My hardware breakdown: as a blog post or on YouTube

Installing software and getting deep learning running on your GPU: as a blog post or on YouTube

Getting your data local on a NAS: as a blog post or where to find data to start with on YouTube.

Here's a few questions that come up in the comments and messages.

Question: Can I start with [insert computer name here]?

Answer: Obviously! I chose my setup because I wanted a consumer-grade GPU for running ML/AI workflows locally. Not every person will want that.

If you don't want to build your own, if you prefer Macs, if you're happy to use cloud-based models, then your workflow will certainly vary. The most important part is to start small on whatever you're thinking of moving local/self-hosted and build on that over time.

Question: How much energy does it pull?

Answer: I'm working on getting specific numbers, but I've been using it for the majority of last year for small workloads and haven't noticed a significant change in my energy bill.

I turn it on with a wakeonlan packet and use it for a job and then I turn it off. I'm a big fan of making sure my machines are off when I'm not using them; for the environment, for security, and for long-term care/maintenance.

Question: What models are you running?

Answer: Usually task specific models or experiments that require more power. For example, I will have an idea of something I want to do (say, try out reading an article out loud for me). I will then look on HuggingFace what the latest models are for such things based on popularity, leader boards and AI/ML companies that I follow.

Then I will turn on the GPU-machine, ssh in, download the model and test it out using Python or Jupyter with whatever data I was thinking of (or sometimes just test data to see if it even works).

If it works well, then I'll write a proper script to go through a whole folder or repeat the inference. At the end, I'll scp the files back to my primary computer or wherever I'm going to use them and then turn off the GPU computer. Rinse and repeat.

I'll be showing some projects this year that I've been tinkering with to give you even more ideas and I'd be excited to hear about any projects or models you've been self-hosting and running locally or with a mixture of local + cloud.

I had a great time at FOSDEM; especially in the AI Plumbers dev room where I learned way more about how GPUs and GPU software works. I also gave my talk titled What do we mean when we say Sovereign AI in the main track.

In the talk, I challenged the AI/tech community to think through what messaging is being sent by large cloud vendors, lobbyists and politicians around sovereign AI/tech. I asked, are these messages stories or facts?

I also added some underserved stories that don't have enough publicity and promotion. I'll share a few here:

The advances made in the past nearly 10 years of federated learning are significant. OSS federated learning libraries like Flower can pretrain large models in federated setups. Google's DiLoCo design demonstrates how federated setups can outperform centralized ones and promote more efficient communication.

The teams I've gotten to know as part of the SPRIN-D Composite Learning Challenge are changing how we calculate data center design, compute and cost requirements for training large models.

This story counters the centralized is best narratives that plague the development of Gigacenters as a necessary step of the digital sovereignty journey.

There is an increasing trend of running AI locally for your own needs on your own data and your own compute. I predict this trend will continue; and it's an amazing tribute to the amount of open-source software, open weight models and available data.

I hope the EU Data Act increases this trend and allows people to build even more useful local AI for their needs. You'll be hearing more from me on this topic, especially on my YouTube channel.

On an individual level, sovereignty means agency, choice and ability, and local-first AI is delivering that.

If better open silicon chips are the future, if renewable energy sources for data centers are important, if privacy and security should be built into AI/ML offerings, then no single player can create all of the requirements.

As I listen to these digital sovereignty conversations from a European perspective, the EU is built on diplomacy, compromise and collaboration. Sadly, these skills are often lacking in today's conversations.

I am still hopeful that digital sovereignty can create new understandings of how, when, where and with whom cloud and data technologies are made. I hope that funding and investment follows new priorities: for a digital future with privacy, with human rights and agency, and with care for our environment and communities.

If you're working in sovereign cloud, I'm always eager to chat and hear about your work and any feedback you have to my talk.

It's a pleasure to read from you; either by a quick reply or a postcard or letter to my PO Box:

Postfach 2 12 67 10124 Berlin Germany

Until next time!

With Love and Privacy, kjam

With Love and Privacy, kjam